The Forgotten Lessons Of Infectious Disease Control

Remembering the 19th and 20th centuries

Eight thousand Americans died of covid in December.

Already in January more Americans have died of covid than die of flu in an entire year.

In the UK, covid’s January death toll will be around one thousand people.

Every week thousands are being left with post covid conditions, including children.

Yet despite these horrifying numbers, more than four years after the start of an airborne pandemic, almost no one is talking about the air.

The thing the virus is in.

Campaigners are trying.

In the UK a mother confronted a Labour politician on radio about child absences from school and asked why she wasn’t recommending schools upgrade air filtration systems to reduce viral particles in the air.

She responded that we need more evidence they work.

In response to demands for clean indoor air, dodgy scientists who have pushed to minimise covid have said there is no good evidence air/HEPA filters work.

In fact there is a mountain of evidence that they work. The study that said they don’t has been discredited.

They’ve been working in many industrial settings for decades. It’s one of the things that enables intensive pig farming.

The Davos elite know they work. Last year Davos was littered with them.

This year they held interviews outside.

The fight for clean air to reduce disease transmission is nothing new.

It is nearly two centuries old.

By the start of the 20th century tuberculosis had killed one out of every seven people who had ever lived.

Tuberculosis is caused by a bacteria, and like the virus that causes covid, it is airborne.

Until the discovery of the tubercule baccilum in 1882, and because its prevalence was so high among families of the same household, it was believed to be a hereditary disease. It was in fact contagious, the bacteria being spread through the air from person to person within a home.

Once this was discovered, public health authorities in the US initiated a countrywide public health campaign in astounding scope and scale. Staggering photos and posters tell the story of this time.

Doctors and nurses toured the country, going into schools and libraries to give presentations to children and the public on what TB was and how it spread. Below is a presentation in a New York city school in 1900.

Public health officials issued pamphlets that stressed the importance of fresh air for children both at home and in schools to prevent the spread of the disease.

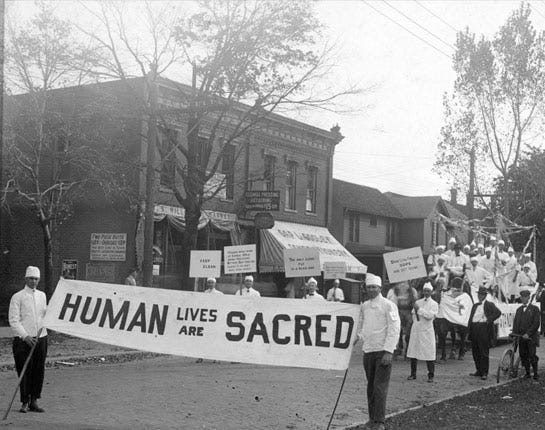

Disease prevention day was inaugurated in the US in 1914, doctors and nurses leading marches around the country to spread awareness about the importance of hygiene, cleanliness and fresh air. This is in Indiana in 1914.

In 1920 the Red Cross commissioned a public health poster presenting it as manly to stop disease from entering your home. The contrast with today’s tough it out, get-sick-to-get-well attitude, is jaw-dropping.

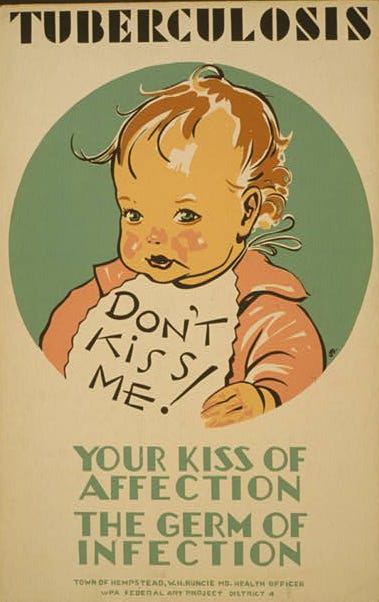

After the second world war, The Works Progress Administration as part of FDR’s New Deal produced startling public health posters warning adults that kissing children risked infecting them with TB.

Anything like this in the current covid context is impossible to imagine.

Unlike the half-hearted 18 month covid public health campaign we witnessed, the TB awareness campaign went on for decades.

Alongside the information campaigns, mass testing programmes were established across the country to locate as many people as possible with TB. Sanatoriums were opened where sufferers could convalesce and recover. It’s even argued that architecture in the first half of the 20th century was heavily influenced by the design of sanatoriums that prioritized windows, through drafts and open spaces, like this one in Kentucky.

And it worked. In 1900 it is estimated there were millions of cases of TB in the US, with nearly 200 deaths for every 100,000 infections. This had reduced to 115,000 cases in 1945 and by 1960 this had halved to 55,000. The rate of death went from 40 per 100,000 people in 1945 to 6 per 100,000 in 1960.

The real kicker is this: such stunning success was achieved without antibiotics or vaccines, which only became available for TB (the BCG vaccine) in the late 40s and early 50s. In the US the BCG vaccine was never used, and to this day is only rarely used.

Social epidemiologist Thomas McKeown found that the mortality rate from tuberculosis in the US had already dropped 91% by the time of significant antibiotic use in the 50s. Antibiotics and vaccination, he concluded, had contributed just 3.2% to the mortality reduction from tuberculosis since the 19th century.

Non-pharmaceutical interventions were the foundation upon which vaccines and treatments built.

The fight against infectious disease one hundred years earlier, in 19th century Britain, like the story of TB in the US, provides stark covid contrasts and parallels.

TB was one of the many infectious diseases that plagued the filthy cities of rapidly industrializing England.

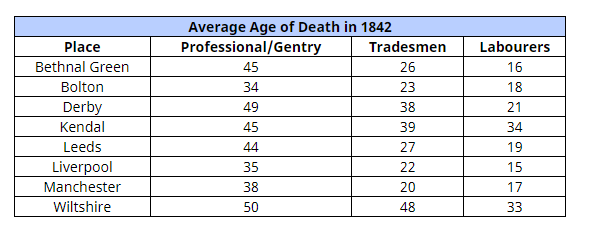

It can be hard to believe just how far life spans crashed during this period. In the first half of the 19th century, average life expectancy in Liverpool for labourers in the city was just fifteen years old. The average for tradesmen was just twenty-two.

While a little better in places like London and Manchester, average life expectancy for labourers in most big cities was under 20 years of age. (Source)

Cities were growing exponentially, trade across the empire was flourishing, but industrialisation wasn’t liberating people. It was immiserating them.

The industrial heartlands of the imperial core were sinks for human life.

Concerned that disease and death was undermining the project of industrialisation, and fearing a revolution among those condemned to live in filth, the British government commissioned Edwin Chadwick to undertake an investigation into the conditions of the working poor.

Chadwick’s Report on The Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain said unsanitary conditions were linked to the spread of disease. No one in this time really knew why. Germ theory wasn’t established and the causes were contested. The leading theory, of which Chadwick was a proponent, was that rotting organic waste created a miasma, or ‘bad air,’ that made people sick.

While he got this wrong, Chadwick understood a basic fact: clean air and water were the keys to reducing disease outbreaks. His report led to the Public Health Act of 1848, under which towns had the power to install sewer systems, ensure constant water supply to homes, and build drainage that carried wastewater outside urban areas for the first time.

The act was highly controversial and opposed by many who saw it as an overbearing intrusion on people’s lives and it was defeated in a parliamentary vote.

The bosses of private companies that supplied fresh water and removed sewage for middle class areas lobbied against the act, their business threatened by a national system of clean water and sewage disposal. Laissez-faire ideology dominated, and politicians argued that if people wanted clean water or sewage removal, that was their choice. Architects fought against Chadwick’s demand that only circular, glazed sewer pipes be used for carrying away water. They said they didn’t work, arguing for traditional square brick pipes, despite all the evidence.

The Times, England’s biggest newspaper at the time, wrote an editorial raging against the idea of “being bullied into health” by the government.

I’m assuming much of this sounds familiar in the context of covid.

Masks are our glazed pipes, the you-do-you attitude on avoiding Sars2 the perfect mirror to the laissez-faire attitudes of the 19th century.

This public health act (which passed the second time), and especially its successor act in 1875 set the stage for sustained reductions in infectious disease and increased life expectancy. And they did so before the advent of modern medicine

A King’s College London/Harvard study found that in 1900 the annual death rates for diphtheria, measles, and pertussis (whooping cough) in the UK were 40, 13, and 12 per 100,000 people respectively. By I960 there were no deaths reported for diphtheria, and only 2 and 1 per 100,000 for measles and pertussis.

The authors point out that: “most of the fall in death rates from measles and pertussis occurred before the introduction of their respective vaccines or the availability of antibiotics.”

We have forgotten that public health gains, especially against infectious disease, have always been fought for, and achieved, in a social context. They have never been gifted to us by medicine.

In 2016 researchers surveyed hundreds of people in the US, asking them how they believed TB had been reduced so dramatically. The majority said the reductions were down to modern medicine. Very few mentioned public health measures.

The researchers said the widespread belief that modern medicine alone rescued humanity from infectious disease is dangerous.

“If society fails to appreciate the important role non-medical interventions played in reducing past infectious diseases, it is likely to continue to attribute modern medicine as the primary vehicle to improve contemporary population health. Conversely, people will be less likely to support public health interventions or policies that seek to improve population health by addressing social determinants of health.”

Vaccinations and treatments give you an extra push away from the illness and death infectious disease brings, but they have never been, and can never be, the basis for public health.

Our public health institutions, many medical professionals and academics, have forgotten this lesson of history. Maybe they never learnt it.

So here we are, in 2024, four years into a pandemic that is being widely ignored because of the very reasons the researchers warned about.

As soon as the vaccine roll-out began, the exhortations to relax and go back to normal started. For many, vaccines meant the pandemic was over. The arrow on this chart of cumulative deaths marks when vaccinations began in the US.

The belief that modern medicine, not public health measures, determine the control of infectious disease, was, and remains, fully in charge at the societal level.

We were led to believe the world had changed for 18 months, when in reality it had changed forever.

Because vaccines, especially since covid, have become a prized object in the culture war, it has become controversial to state an historical fact: infectious diseases of the past were defanged by public health measures, not pharmaceutical ones.

Our public health institutions need to relearn this lesson, or learn it for the first time. And do it quickly.

Because every day the burden of covid grows, for individuals, families and for societies. It is now hobbling economies, with Germany falling into recession due to worker sickness.

Vaccines and treatments should be the last line of public health defence, not the first.

If you make them the first, as our governments are now doing for covid, they will fail quickly, and they will fail repeatedly.

How much more failure is necessary before public health authorities return to doing the job they were set up to do?

With regards to tuberculosis, there are excellent counterexamples from places that were unable to institute public health reforms. Even with access to antibiotics, these countries suffer under immense tuberculosis burdens in the modern day. I'm a tuberculosis researcher, and we're still struggling to bring down TB cases using antibiotics alone.

While I can't find the citation right now, I recall that South Africa was a strong example that had relatively comprehensive antibiotic access in the mid- to late-20th century. However, public health infrastructure changes were not made, and thus the TB burden remains high to this day. With high burden comes higher chances of antibiotic resistance, and resistant TB is an important global health threat. So if we don't address these problems that COVID is making clear to us today, we're going to have even more trouble from these previously "defeated" diseases.

As always, great read. For another example from the 19th century, economist Jason Barr and I have been looking at the late 19th and early 20th century tenement acts in NYC. While the results are preliminary, the wards (neighborhoods) with the most new construction - which would be buildings in compliance with better standards of ventilation and sanitation mandated by the tenement acts - have far lower rates of infectious disease mortality than wards with older less ventilated, less sanitary building stock. The wards that were safer and had the most new construction had the most dense living conditions in the city and were some of the most impoverished neighborhoods. So, there seems to be good evidence that the new building standards had a large effect on keeping people safer. We have a two part blog story on this. The first demonstrates the difference across neighborhoods, the second discusses our initial investigation into why the difference existed.

https://troytassier.substack.com/p/how-deadly-were-gothams-tenements

https://troytassier.substack.com/p/how-deadly-were-gothams-tenements-512