Do Max Harm: The Grave Ethics Problem In Healthcare

There have been a million and one US election hot takes so I’m not going to do that, not right now. We’re all saturated with them at the moment.

I wanted first to get to something that has been on my mind for a few weeks, and that’s the troubling frequency with which healthcare workers are accused of and charged with serious and sometimes horrifying crimes, usually crimes against the bodies of other people.

Trigger/content warning here.

When I started researching this I expected there to be plenty of material, but the number of very recent stories I found by searching ‘doctor/nurse charged with’ or ‘doctor/nurse accused of’ was absolutely unbelievable.

I began thinking about it after reading that one of the men who raped Gisèle Pélicot, the French woman who for years was drugged by her husband and raped by strangers, was a nurse. Then a few weeks later my partner read out a story about a Swedish doctor who drugged and kidnapped a woman to keep as his sex slave.

So I began researching individual cases and what I found makes me wonder what we’re actually dealing with here.

There’s the story of the Ohio doctor charged with murdering 25 patients by overdosing them on fentanyl. The story of the woman who set up a hidden camera to document the sexual assaults by her spinal specialist. The doctor in Maine accused of running a massage parlour as a front for prostitution. The Orange County liver specialist charged with groping. The youth hockey doctor in Detroit accused of sexually abusing 27 young men and boys. The doctor in Sacramento accused of abusing his power to coerce his patients into sex. The Pennsylvania nurse who killed 4 patients with insulin overdoses. The Florida doctor accused of stealing thousands in donations meant for Hurricane Helene victims. The US army doctor accused of hundreds of sexual assaults. The doctor in New Hampshire accused of over 200 sexual assaults while working at the acclaimed Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Other headlines include:

Kalamazoo doctor charged for role in telehealth fraud scheme

Jury selected for Regina-area chiropractor's sexual assault trial

There’s also the controversial case of nurse Lucy Letby in England who was recently convicted of killing seven babies.

You get the point.

All of these cases are from the last year or two. This isn’t deep history. This isn’t me avidly researching to find the evidence to support a hypothesis. This is the first few pages on English-language Google. This isn’t, therefore, even the tip of the tip of the iceberg.

If these stories kept cropping up in any other profession, say if airline pilots were regularly being charged with sexual assault, we’d rightly wonder if that industry had a major ethics problem that needed serious investigation. One profession where questions have been raised about a culture of violent crime is the police. Yet there’s a curious difference in how media and wider society treats cases of police misconduct and violence compared to misconduct in healthcare. When it comes to the police, we get (correct) analysis about how a culture of violence and impunity both encourages the wrong people into these jobs and protects them in their criminal behaviour. Even those who deny the police have a systemic problem and write these individuals off as ‘bad apples’ are forced to engage with the issue because the problem has been elevated within our culture to one of importance and visibility.

Nothing of the sort has happened for the medical profession. There is no public debate, no articles, not even the ‘bad apples’ debate. Nothing.

These anecdotal stories would be bad enough on their own, and it would be easier to write them off as statistically inevitable bad apples in one of the world’s largest industries, in the absence of a larger, more obviously systemic issue: healthcare workers aren’t wearing masks on the job in the era of covid. To put it more bluntly, healthcare workers are killing patients. And they are likely killing them en masse.

We don’t have much data about hospital-acquired covid because most countries stopped collecting it when they stopped testing, but Wales didn’t. And in Wales, an incredible near 70% of patients who needed hospital treatment for covid in recent weeks caught covid while in a hospital.

As for deaths from hospital-acquired covid, we’re flying blind since the great unmasking. But anecdotally, it is not uncommon for someone on Twitter to report a friend or family member died of covid caught in a hospital. In January local press in Cornwall, England reported on a man who died from covid he contracted from hospital, but we only found out because of the inquest triggered by his 20-hour wait for an ambulance. The number of deaths via hospital-acquired covid globally is sure to be staggering.

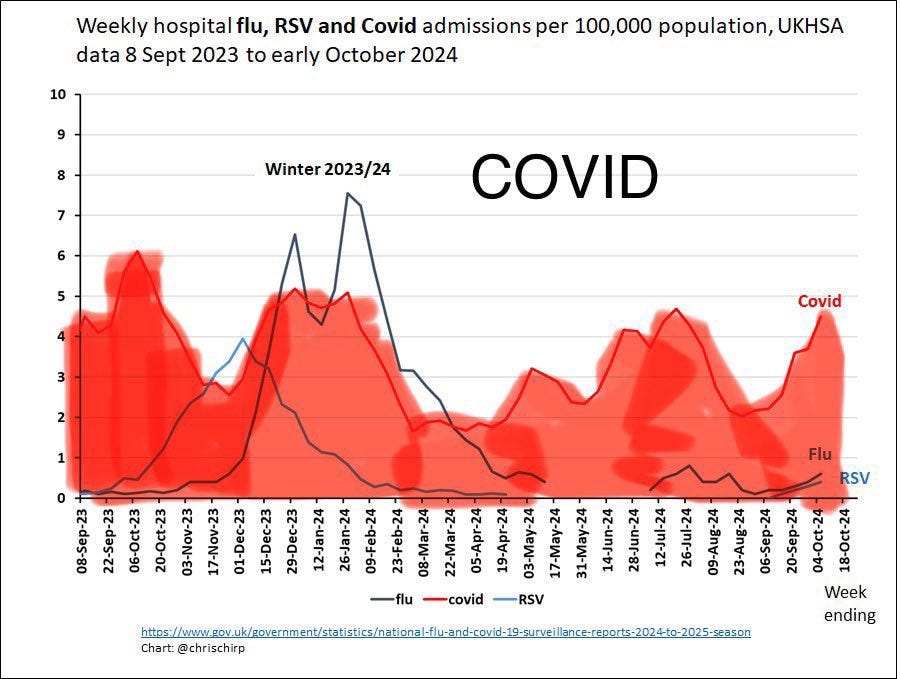

Covid is a year round disease, the virus is constantly mutating and it is ten times deadlier than the flu, with a far higher chronic illness outcome than the flu. (Here’s a chart of hospitalisations for covid vs flu vs RSV in England & Wales for the past 13 months, for any doubters).

Healthcare workers who don’t wear masks that have been proven to work are participating in a structure of aggression and violence that appears, when viewed alongside individual cases where the bar is met for prosecution, to be systemic.

I’m going to make another connection here, and it’s a connection some may not like.

Historians of Nazi Germany say that physicians and others in the medical profession were the most enthusiastic about the Nazi programme to create a super Aryan race. This is borne out by an astonishing statistic: more than half of all qualified German physicians became early joiners of the Nazi Party, surpassing enrollments of all other professions.

The atrocities perpetrated by Nazi Germany, including forced sterilisation, the Aktion T4 programme of mass murder of the mentally and physically sick, and finally the Holocaust itself, were contingent upon the skills, such as we can call them that, of the medical profession. The horror and barbarity of Nazi Germany simply could not have happened without the wilful and even enthusiastic support of large numbers of doctors, nurses and other healthcare workers.

And if we think the sorts of people attracted to jobs where they can have positions of influence and power over other people’s bodies are confined to the past, we’re living in a dream world. If you think these people don’t exist in the enlightened 21st century, you’re in denial. There are many many people attracted, lustfully attracted, to having the power of life and death over another person.

We only have to look at Canada’s MAiD euthanasia programme to find present day examples of extremely troubling character traits among people attracted to ending lives. Earlier this year researchers interviewed physicians who administer euthanising drugs in Canada to glean insights about their state of mind and reaction to what is assumed to be traumatising work. The results were disturbing. Some described feeling ‘an adrenaline rush’ at the moment of death, others said that watching someone die was ‘liberating.’ Some said they laugh together when discussing how to force euthanasia on reluctant patients and their families. One person said administering the lethal drugs causes for them ‘an urgent and pressing need for sex.’ Utterly vile and depraved stuff.

There’s a whole Wikipedia category on medical serial killers.

Then there are the doctors and specialists who write off chronically ill people, a decades-old problem given a spurt of energy with the rise of long covid. Doctors and specialists who threw children with myalgic encephalomyelitis in a swimming pool to prove they'd move under duress. They sank.

It really does appear that there are far too many people who work as GPs, as doctors, as nurses, as specialists, who are ethically and morally compromised. And some, as those individual stories demonstrate, are outright monsters who display clearly sociopathic and psychopathic traits. Some who, for want of a better word, are actually just evil.

Does the healthcare industry have a significant and likely under-reported ethical problem? It seems entirely likely to me. None of this is to trash the reputation of the many good people who care about patients and would never commit a crime or act unethically. And some would argue that with so many people working in this industry, there will, statistically, be a larger cohort of offenders. But why should the size of the industry be an excuse? Why should we allow for an overweighting of criminal behaviour? If any profession should attract people with the highest ethical and moral standards, it should be the medical profession.

Some might argue safeguards are in place in the form of watchdogs and other institutional bodies. But if they were working wouldn’t there be some controversy around the lack of covid infection control in hospitals? Some discussion even?

All of this prompts many questions.

How many ethical scandals in healthcare are waiting to be uncovered?

How many will never be discovered?

Just how pervasive is the problem?

How do you fix it?

How do you make healthcare a less attractive profession to psychopaths?

The need to have this conversation is only becoming more urgent and pressing in the light of forever covid, the rapid increase in chronic illnesses, and the moves to make euthanasia legal in more western countries. In the UK it is expected the new Labour government will legalise the practice in the next few years.

We’re told the first step before tackling a problem is that you have to acknowledge there’s a problem in the first place.

Are our societies willing to go there?

The evidence for that at least is strong. And the answer is no. At least not yet.

Interesting. I’ve been confounded about why health care colleagues aren’t masking. Once we knew we could prevent respiratory illness it should be standard of care but I still not. I know medical training tends to enforce conformity but it’s been astonishing to me to see which of my colleagues refuse to mask up.

My mother was killed by unmasked medical staff who were TESTING HER FOR LUNG CANCER.

Which, miraculously she did not have after 70 years of chainsmoking, but she was dead in a week from Covid. Was she 83, frail, an alcoholic and chain smoker who made my life a trial for decades and was probably going to die of those conditions in the next few months? Yes. But as Jacqueline Rose discusses in her book The Plague, she was, as Freud described it, robbed of her own death. I'll never stop being pissed off about it.